Reread of The Aspect-Emperor Series

Book 1: The Judging Eye

by R. Scott Bakker

Chapter Thirteen

Condia

Welcome to Chapter Thirteen of my reread. Click here if you missed Chapter Twelve!

Damnation follows not from the bare utterance of sorcery, for nothing is bare in this world. No act is so wicked, no abomination so obscene, as to lie beyond the salvation of my Name

—ANASÛRIMBOR KELLHUS, NOVUM ARCANUM

My Thoughts

So we have Kellhus’s justification for why sorcerery is cool these days. And, if I understand the rules of this world, if enough humans believe this, it will happen. We know the Inchoroi wrote the Tusk to make their task easier, and before the Tusk there were Shamans. Prophets and Sorcerer both. But then the Tusk comes along and condemns them. It’s the dominant belief, and now Sorcery is damned. However, I don’t think Kellhus accomplished his goal of actually making sorcery not damnable. Too many people still believe the opposite. Either way, he is convincing the Few that they are not going to be damned and that’s all he cares about.

Now, how does this quote relate to the chapter? Well, Sorweel is getting to know his new tutor in this chapter. A Mandate Schoolman. He’s dealing with something he considers an abomination. This is to give us the start of the New Empire’s view on it versus Sorweel’s, which he’ll be grappling with.

Is Kellhus God and thus able to make that proclamation?

Early Spring, 19 New Imperial Year (4132 Year-of-the-Tusk), Momemn

Sorweel’s people despise scholars, calling them hunched ones and see it as a disease. None are weaker than a “hunched one.” Sorweel’s new tutor isn’t just a hunched one but a Three Seas Schoolman. This is a problem. Sorweel believes the Tusk that “sorcerers were the walking damned.” Still, he has always been secretly fascinated with sorcery. He wonders, “What kind of man would exchange his soul for that kind of diabolical power?”

As a result, Eskeles was both an insult and a kind of illicit opportunity—a contradiction, like all things Three Seas.

Not long after the day’s march started, Eskeles would begin teaching Sorweel Sheyic. It’s mind-numbing tedium. He comes to dread these lessons. He even asks Zsoronga to hide him, but the Successor-Prince betrays Sorweel, wanting to be able to speak to Horse-King without going through Obotegwa. Sorweel finds Eskeles strange. He’s fat by Sakarpi standards but there are fatter men in the Great Ordeal. Despite wearing silk and leggings, his robe is open leaving his chest exposed to the cold. But he never seems cold. He’s a friendly and merry man. He’s hard to dislike despite being a sorcerer and a Ketyai.

Eskeles learned Sakarpi while being a Mandate spy posing as Three Sea traders to the city. He says it was a dreadful time. Sorweel thinks because it doesn’t have “Southron luxuries” but it’s because of the Chorae horde. He calls them trinkets.

“Trinkets?”

“Yes. That’s what we Schoolmen like to call them—Chorae, that is. For much the same reason you Sakarpi call Sranc—what is it? Oh, yes, grass-rats.”

Sorweel frowned. “Because that’s what they are.”

Despite his good humour, Eskeles had this sly way of appraising him [Sorweel] sometimes, as if he were a map fetched from the fire. Something that had to be read around burns.

“No-no. Because that’s what you need them to be.”

Sorweel understood full well what the fat man meant—men often used glib words to shrink great and terrible things—but the true lesson, he realized, was quite different. He resolved never to forget that Eskeles was a spy. That he was an agent of the Aspect-Emperor.

Sorweel discovers learning another language is hard as he discovers grammar for the first time. He learns how his own language is constructed so he can then learn how others are. He pretends to be aloof (he is with a hunched one) but is disturbed how he could know grammar without knowing it. “And if something as profound as grammar could escape his awareness—to the point where it had simply not existed—what else was lurking in the nethers of his soul?”

So he came to realize that learning a language was perhaps the most profound thing a man could do. Not only did it require wrapping different sounds around the very movement of your soul, it involved learning things somehow already known, as though much of what he was somehow existed apart from him. A kind of enlightenment accompanied these first lessons, a deeper understanding of self.

It still was boring. Luckily, even Eskeles would tire of it by afternoon. Then Sorweel could satisfy his own curiosity. All save the one that fascinated him the most: sorcerery. He learned about the various people of the Great Ordeal. As he did, Sorweel realized that Eskeles “discussed all these people with the confidence and wicked cynicism of someone who had spent his life traveling.” And, despite being vain, Eskeles wasn’t arrogant. He’s honest about the strengths and weaknesses of each nation.

Finally, after several days, Sorweel dares to ask about Kellhus, starting with an abridged version of the emissaries to Zeüm who slit their throats. He’s awkward as he wants to know what Kellhus is. Eskeles nods as if he had worried this question would come up and tells Sorweel to come with him. Since the Kidruhil ride on the front of the left flank, it doesn’t take the pair long bore they are riding ahead of the host. They climb a knoll from where the plains stretch to the horizon, the land looking dead. No longer the green of the lands to the south. Eskeles point out and asks what is out there. He peers out and then sees the great herds of elk that cover the plains in countless numbers. Then Eskeles turns and points back at the Great Ordeal and asks what that is. He turns back and is confused. He sees countless men stretching back to the horizon.

“The Great Ordeal,” he heard himself say.

“No.”

Sorweel searched his tutor’s smiling eyes.

“This,” Eskeles explained, “this… is the Aspect-Emperor.”

Sorweel keeps staring at them but he doesn’t understand. Eskeles says there are many ways to divide up the world, saying this part belongs to this man and so on. But what if you did that with his thoughts. Where does a man’s idea begin and end? Sorweel’s brain hurts, still confused. Eskeles dismounts and starts fishing in his mule’s rump pack. He produces a small vase. Sorweel is dismissive of it as “another luxury of the Three Seas.” Eskeles tells him to come and then searches for a stone rising out of the grass. He calls the vase a philauta used for sacramental libations. As he raises it, Sorweel sees little golden tusks on it and hears something rattling inside. Sorweel flinches when Eskeles shatters it on the stone. He tells Sorweel to stud the various pieces. Eskeles picks a splinter up.

“Souls have shapes, Sorweel. Think of how I differ from you”—he raised another splinter to illustrate the contrast—“or how you differ from Zsoronga,” he said, raising yet another. “Or”—he plucked a far larger fragment—“think of all the Hundred Gods, and how they differ from one another, Yatwer and Gilgaöl. Or Momas and Ajokli.” With each name, he raised yet another coin-sized Fragment.

“Our God… the God, is broken into innumerable pieces. And this is what gives us life, what makes you, me, even the lowliest slave, sacred.” He cupped several pieces in a meaty palm. “We’re not equal, most assuredly not, but we remain fragments of God nonetheless.”

He asks Sorweel if he understands. The boy does. More than he wanted. “The Kiünnatic Priests had only rules and stories—nothing like this.” Eskeles makes too much sense. He wants to object, but he can’t. Eskeles continues his lesson by asking what is the Aspect-Emperor. He gathers up a chipped replica of the original that had been inside rattling around.

“Huh?” The Schoolman laughed. “Eh? Do you see? The soul of the Aspect-Emperor is not only greater than the souls of Men, it possesses the very shape of the Ur-Soul.”

“You mean… your God of Gods.”

“Our God of Gods?” the sorcerer repeated, shaking his head. “I keep forgetting that you’re a heathen! I suppose you think Inri Sejenus is some kind of demon as well!”

Sorweel feels embarrassed and says he’s trying to understand. Eskeles says they’ll discuss Inri Sejenus and says Kellhus is soul is the same shape as the God. He prompts Sorweel to say, “He is the God in small…” That terrifies Sorweel saying it. Eskeles is proud and says this is why people cut their throats for him and all these tens of thousands march behind him. “Anasûrimbor Kellhus is the God of Gods, Sorweel, come to walk among us.” This causes Sorweel to collapse to his knees. He feels fragile, on the verge of falling apart.

Eskeles continues how sorcerers used to be damned. “We Schoolmen traded a lifetime of power for an eternity of torment… But now?” Sorweel thinks of his father being killed by sorcery and wonders if Harweel is still burning from it because sorcerery is damned. However, Eskeles’s eyes are full of “uncompromising joy.” It’s the look of someone who has been rescued. He speaks with worship now.

“Now I am saved.”

Love. He spoke with love.

He keeps thinking that Kellhus is God walking among them as he eats his meal with Porsparian. “Men often make decisions in the wake of significant events, if only to pretend they had some control over their own transformations.” So Sorweel decides to ignore it, as if being rude to Eskeles would stop the process. Then the youth laughs but it peters out.

Then he finally decided to think Eskeles’s thoughts, if only to pretend they had not already possessed him. What was the harm of thinking?

As a boy, he once found a poplar seed beneath a bush. He would watch it as it slowly grew, destroying the bush in the process. When his city fell, it had become a big tree and he realizes, “There was harm in thinking.” He feels what Eskeles has spoken is true. The Mandate Schoolman’s explanation makes too much sense. That even Sorweel is a piece of God. He realizes this is why the Kiünnatic Priests had demanded Kellhus’s missionaries to be burned.

Had they been a bush, fearful of the tree in their midst?

As he lies beneath his blankets, he relieves his first meeting with Kellhus and fears that he’ll come to believe in Kellhus like the others.

When he wakes up, he feels relief instead of a clutch of fear. For a moment, there is only silence and then the Interval tolls for morning prayers. Soon there are drills and his pony is finally responding to Sakarpic riding commands. He has no problem with the drills this morning and is called Horse-King.

When chance afforded he leaned forward to whisper the Third Prayer to Husyelt into the pony’s twitching ear. “One and one are one,” he explained to the beast afterward. “You are learning, Stubborn. One horse and one man make one warrior.”

He suddenly feels shame. He’s not a man since he never has, and never will, go through his Elking. “A child forever without the shades of the dead to assist him.” He glances at the wonder of the Great Ordeal and feels small.

Later, as he’s riding with Zsoronga and Obotegwa, he asks what the Successor-Prince thinks of the Ordeal. Zsoronga thinks it’s their end. Sorweel asks if Zsoronga thinks their goal is a real one. The Ordeal believes it. He’s not sure how Sorweel sees it from his one city, but Zeüm is a nation mightier than any other and he’s never seen anything like this. No Satakhan could ever have gathered so many and marched them to the world’s end. This event will be “[r]ecalled to the end of all time.” After some silence, Sorweel asks what Zsoronga thinks of the Anasûrimbor.

The Successor-Prince shrugged, bunt without, Sorweel noticed, a quick glance around him. “Everyone ponders them. They are like the mummers the Ketyai are so found of, standing before the amphitheater of the world.”

Everyone thinks he’s a Prophet or God. Sorweel asks but what does Zsoronga think. He quotes the treaty Kellhus made with Zsoronga’s father. Kellhus is the “Benefactor of High Holy Zeüm, Guardian of the Son of Heaven’s Son.” Sorweel presses for a real answer. Zsoronga asks what Sorweel thinks about Kellhus.

“He’s so many things to so many people,” Sorweel found himself blurting. “I know not what to think. All I know is that those that time with him, any time with him whatsoever, think him some kind of God.”

As Zsoronga confers with Obotegwa in their tongue, Sorweel realizes that Zsoronga is a spy and he, Sorweel, is but a distraction to the Successor-Prince. Zsoronga looks at Sorweel like the Successor-Prince wants the Horse-King to be a trustworthy ally.

Finally, Zsoronga asks if Sorweel’s heard of Shimeh’s fall in the First Holy war. Sorweel shrugs and says not much. Zsoronga brings up Achamian’s “forbidden book.” Zsoronga explains that Achamian had been Kellhus’s teacher and that the Empress had been Achamian’s wife, stolen from him by Kellhus. He adds how Achamian declared Kellhus a fraud and a liar. Sorweel has heard something of that. Achamian only lives because “the love and shame of the Empress prevent his execution.” Zsoronga laments that while his book rings true, it’s also the bitter account of a cuckold that casts doubt on it. Still, Sorweel has to know if Achamian thought Kellhus a demon but learns he doesn’t. Sorweel begs to know exactly what Achamian, pleading his friendship with Zsoronga to get the Successor-Prince to speak.

The Successor-Prince somehow grinned and scowled at once. “You must learn, Horse-King. Too many wolves prowl these columns. I appreciate your honesty, your overture, I truly do, but when you speak like this… I… I fear for you.”

Obotegwa had softened his sovereign’s tone, of course. No matter how diligently the Obligate tried to recreate the tenor of his Prince’s discourse, his voice always bore the imprint of long and oft-examined life.

Still, Sorweel wants to know what Achamian wrote. Zsoronga finally answers him that Kellhus is a mortal man with a vast intellect that makes others seem children. Sorweel presses for more. Zsoronga says, “The important thing, he [Achamian] says, isn’t so much what the Anasûrimbor is, as what we are to him.” Sorweel is frustrated by the answer. He urges Sorweel to remember what being a child was like and how you believed nursemaid’s tales and your emotions always were on your face. How adults had molded you. Kellhus is the adult and everyone is a child.

Zsoronga dropped his reins, waved his arms out in grand gesture of indication. “All of this. This divinity. This apocalypse. This… religion he has created. They are the kinds of lies we tell children to assure they act in accord with our wishes. To make us love, to incite us to sacrifice. This is what Drusas Achamian seems to be saying.”

These words, spoken through the lense of wise and weary confidence that was Obotegwa, chills Sorweel to the pith. Demons were so much easier! This… this…

How does a child war against a father? How does a child not… love?”

This dismays Sorweel and shames him, though he realizes Zsoronga feels the same way. Sorweel then asks what Kellhus’s true goal is. Achamian never said, though Zsoronga fears they’ll learn by the end.

Sorweel dreams of his father arguing with Proyas from the earlier chapter when Proyas came to parley. They are feuding about bondage. Proyas says there is slavery that sets one frees, which Harweel denounces, “So says the slave!” Harweel shouts while burning. Sorweel thinks, “How beautiful was his [Harweel’s] damnation.”

Porsparian wakes Sorweel from his nightmare and soothes the prince. He tells the uncomprehending slave he saw his father burning. Porsparian’s touch feels grandfatherly and comforting. He asks if his father is damned. “A grandfather, it seemed, would know.” Porsparian forms the feminine face of Yatwer in the dirt of the tent floor. He then rubs dirt on his eyes and prayers, rocking back and forth “like a man struggling against the ropes that bound him.” The sun rises, lighting up the tent as the slave keeps praying. Porsparian’s movement grows jerky. Violent. He spasms and convulses. Worried, Sorweel leaps to his feet and cried out in concern.

But he feels the ritual’s rules demand he not interfere, so he just watches. Porsparian is writhing on the ground like he’s being beaten. Then, he suddenly springs upright and pulls his dirty hands from his eyes. They are stained red. Then he looks down.

Gazed at the earthen face.

Sorweel caught his breath, blinked as though to squint away the madness. Not only had the salve’s eyes gone red (a trick, some kind of trick!), somehow the mouth pressed into the soil face had opened.

Opened?

There’s water pooled in the mouth that pours into Porsparian’s palm, his eyes no longer red. “Muck trailed like blood from the pads of his [Porsparian’s] fingers.” Sorweel backs away. Suddenly, the slave seems made of river mud. He says this is spit to keep face clean. It will hide him. Suddenly, Sorweel understands that the Old Gods are protecting him. He closes his eyes and the mud is smeared on his cheeks. “He felt her spit at once soil and cleanse.”

A mother wiping the face of her beloved son.

Look at you…

Somewhere on the plain, the priests sound the Interval: a single note tolling pure and deep over landscapes of tented confusion. The sun was rising.

My Thoughts

Grass-rats. I do like that name for Sranc. Sorweel, is of course, right. We give glib names to terrible things. Or grand things. We like to minimize. Like America and England like to call the Atlantic “the Pond” as if it was just this small thing separating our two countries.

There is a lot of things humans do without thinking about it. Language is the most unique trait of our species. No other creature on earth has language. They can communicate, but even the gorillas and chimpanzees who have been taught sign language can only string together a few words to form a very basic idea. They can’t speak with the complexity and nuance of grammar. This is hard-coded into human beings when we’re young. English, despite its large vocabulary, has had its grammar flattened to an extent. You would not realize this if you only spoke English, but our complicated grammar is simple compared to a many other languages. Some can have such a complexity to it only native speakers can ever grasp its nuance. It actually seems the more a language is spoken by only a small group of people, the more and more complicated it becomes.

While Sorweel has this vast revelation about knowledge, I know when I studied German, I didn’t have any profound epiphany on the nature of reality. However, it does tie into the greater theme of the Second Apocalypse: how little men understand why they do the things they do. Language has always been a large part of the series. Just notice the appendix at the end of The Thousandfold Thought that shows the family tree of the languages of men. It also ties into the fact that sorcerery requires learning another language that buffers the purity of meaning from the way a spoken language drifts and meanders. Words change so drastically, sometimes in a generation, and can come to mean even their opposites or something wholly alien.

Eskeles has a mule like Achamian. He’s very much a surrogate for that role, teaching Sorweel while during a holy war. Only Sorweel is the opposite of the Young Prince trope that Kellhus was. Neither one of them fulfill the trope but subvert it in different ways. Sorweel never avenges his father. He dies a failure. Though, he did get the princess before the end. I think that decision is one of the reasons Serwa behaves as she does during the climax of the Unholy Consult.

We can see Eskeles’s disregard for wealth and comfort. He breaks a rather expensive looking vase without thought to teach a lesson to his pupil. Eskeles might dress in silks and be fat, but he’s a man that has lived without much and understands how possessions can weigh you down.

Ideas have no boundaries. They spill from person to person. You can’t contain them. Can’t segment them. They spread as new people encounter them and embrace them or discard them. It is honestly why the idea of “Cultural Appropriation” is such a problem. The very act of strangers coming together rubs off some of their cultures on each other. It morphs and mutates and changes into new ideas (or bad ones). The more human cultures mix and exchange, the more advancements we make. Strangers can see what is common to one group in a new light and make a breakthrough in so many different areas. Haven’t you ever been stuck on a problem only for “fresh eyes” to easily spot what you’re missing?

And now we see Baker reinforcing for us, the readers, on his world’s metaphysics. Reminding us that the God is broken into an innumerable amount of pieces, each one inside of a person and peering out through their eyes. This is why his sorcery works. Those who can use sorcery are better able to see with “God’s Eye”. It’s also how Mimara’s Judging Eye works. Destroying this Oversoul is the goal of the Consult and the Inchoroi. With it gone, so are the effects of its existence.

Namely Damnation.

Eskeles speaks with all the conviction of the newly converted. There are none more fervent than those who have abandoned their past belief in favor of a new one. To have so changed their identity takes something powerful on their psyche, so they will really embarrass the new belief. If it’s a dangerous belief, this can be bad. As Dr. James Lindsey describes it, religions can come in two flavors. Those that look up and those that look down. A religion that looks up is one that’s about self-improvement. Being a better person. A religion that looks down is concerned with making sure your neighbors are being virtuous. You could say Jesus’s teachings are an upward-facing religion but many have turned it into a downward-facing one and used it to unleash horrors like the Inquisition or the Witch Hunts. Or the Teutonic Knights’ crusades in Eastern Europe.

The poplar metaphor is fairly obvious. That’s how ideas can work. If they get past your defenses, they can sprout and change you. It can be painful, but once it starts it’s hard to stop.

The Great Ordeal will be recalled until the end of time. But who will recall it? Given how this series ends, will there be anything left? We’ll have to wait and see for the third series.

Zsoronga sees the Dûnyain as performing. That’s very interesting. He comes from a culture that enjoys performing and acting differently in their day to day life. It makes him suspicious of everyone’s actions, I assume. Doubly so of a man claiming such inhuman piety. Sorweel’s answer to that Kellhus mummers (theater acting) is on point.

I do like the added bits of the problem with going through a translator. The words just don’t have the same effect coming from another’s mouth. And why should they? Another person can’t mimic the passions of the person for whom they’re speaking.

Zsoronga’s quote about the lies we tell children in regards to a religious holy war should probably let you know Bakker’s thoughts on religion. We lie to our children to control them, and religion lies to adults for the same reason. Kellhus is just really good at lying.

“How beautiful was his [Harweel’s] damnation.” Sorweel dreams of his father’s damnation was beautiful. His father had never surrendered to Kellhus. Had never succumbed to Kellhus. Sorweel, the perpetual child, has to his new father and that shames him to no end. So he dreams of his father’s defiance and sees it as beautiful. A stubbornness to refuse to bend no matter the cost.

Notice how the mud is like blood on Porsparian’s fingers. We’ve seen in the ritual creating the White Luck Warrior the importance of menstrual blood in Yatwerian rites. And it does hide him. Even Kellhus is fooled. It just doesn’t work. We hear a lot about Narindar, holy assassins, and that is what Sorweel is. He’s being used by Yatwer to kill Kellhus. Another young man being sacrificed.

Sorweel mentions how he’ll forever be a child. That’s how Yatwer is treating him.

Want to keep reading, click here for Chapter 14!

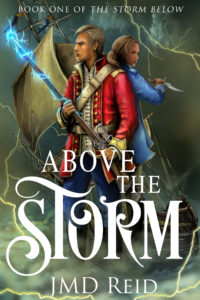

And you have to check out my fantasy novel, Above the Storm!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

…Ary’s people have little chance.

Can he find a way to defeat them?

At 19, Ary has spent ten years mourning his father’s death. The aftermath of the attack still haunts him. Now, on the eve of the draft he faces his greatest fear, being sent to become a marine.

He knows the cost of war.

All he wants is to marry Charlene, who he has loved since they were kids. Building a farm and starting a family sounds perfect. There’s just one problem, his best friend Vel adores her, too. He’d give anything for peace.

But wanting the Stormriders to stop attacking…

…isn’t going to make it happen.

For love, for his people, and especially for the life he wants, Ary makes a decision that will change everything.

The adventure begins.

You’ll love this beautifully creative dark fantasy, because James Reid knows how to create characters and worlds you’ll grow to adore.

Get it now.

You can buy or burrow Above the Storm today!