Reread of The Aspect-Emperor Series

Book 1: The Judging Eye

by R. Scott Bakker

Chapter Fourteen

Cil-Aujas

Welcome to Chapter Fourteen of my reread. Click here if you missed Chapter Thirteen!

The world is only as deep as we can see. This is why fools think themselves profound. This is why terror is the passion of revelation.

—AJENCIS, THE THIRD ANALYTIC OF MEN

My Thoughts

What an interesting quote to start the chapter of Achamian’s company moving through Cil-Aujas.

I think we all have met people who think they are smarter than they are, who believe they know everything, or think the pretentious and inane things they are posting on Twitter (cough Jayden Smith cough) are mind-blowing. Now, the second half of this quote about terror being revelation’s passion is the intriguing part.

It implies, to me, that terror is what drives revelation. The fear of the unknown drives us to want answers. To have the darkness revealed to be something that we can understand. The fool will latch onto ideas that are not logical. The divine, for instance.

Bakker uses REVELATION. That carries the connotation of Moses and the Burning Bush. God telling you what’s up. The fool, terrified of what is around him, latches onto anything to make his fears lessen. Any explanation that their small minds see as profound. Even if it is shallow.

So, how does this fit into the chapter?

Well, we definitely have a lot of small minds heading into a place of sheer terror. Let’s not even consider the fact that it’s a topoi that has trapped the souls of the Nonmen murdered by treacherous humans and that hell itself is bleeding into the place. Just being underground is unnerving. If you’ve ever been in a cave or a mine shaft, it can creepy with all that stone over your head. And you do not know what darkness is until you find yourself in a lightless mine shaft. When I was a boy scout back in New Mexico, we went into an abandoned cinnabar mine on a camping treat. Most of us had flashlights. I did not. Everyone turned theirs off.

It was a complete darkness and it had weight. It was terrifying, and I knew there were people around me that had light sources.

Then we take into account the messed up stuff that’s about to happen and, as I assume we’ll see, we’re going to find scalpers (cough Sarl cough) making up stories to explain the strange things. The horrors. They will latch onto a revelation to carry them through the darkness.

And now reading the chapter, it’s a perfect quote because revealing what is really going on only inspires terror and threatens to break the Skin Eaters.

Spring, 20 New Imperial Year (4132 Year-of-the-Tusk), south of Mount Aenaratiol

Age. Age and darkness.

The Chronicles of the Tusk is the measure of something ancient to humans, but now in Cil-Aujas, the Skin Eaters are discovering a place older than the language of the Tusk. “Here was glory that no human, tribe or nation, could hope to match, and their hearts balked at the admission.” Achamian sees it in their eyes. All their boasting is now proving lies.

Cil-Aujas, for all its silence, boomed otherwise.

The company is moving through a subterranean. The trails after the Cleric and Achamian who both have sorcerous lights before them to illuminate the dark. Every sound brings cringes. Every inch of wall is covered in images, the tunnel hacked out of the mountain.

It was the absence of weathering that distinguished the hall from the Gate. The detail baffled the eye, from the mail of the Nonmen warriors to the hair of the human slaves. Scars striping knuckles. Tears lining supplicants’ cheeks. Everything had been rendered with maniacal intricacy. The effect was too lifelike, Achamian decided, the concentration too obsessive. The scenes did not so much celebrate or portray, it seemed, as reveal, to the point where it hurt to watch the passing sweep of images, parade stacked upon parade, entire hosts carved man for man, victim for victim, warring without breath or clamour.

This is Pir-Pahal, a room memorializing the Nonmen’s war with the Inchoroi. Achamian spots the traitor Nin’janjin (the guy who gave sold immortality to the Nonmen) and Cû’jara-Cinmoi. Even Sil, the Inchoroi King, is shown holding the Heron Spear which makes Achamian stumble. Mimara is unnerved by the sight of the Inchoroi. Achamian realizes, remembering the Great Ordeal marches for Golgotterath, that the war shown here has never ended.

Ten thousand years of woe.

Achamian explains that the Nonman carved their memories into the walls to last as long as they. Many are not happy that Achamian broke the “sacred” silence. They head deeper, covering miles. Then they come across a gate carved with a pair of wolves. These are more totemic than past carvings, each wolf carved three times to show them flowing from three different emotions to capture a living creature in stone. The writing here is Auja-Gilcûnni, the First Tongue. So ancient, not even the Nonmen can read it which “meant this gate had to be as ancient to Nonmen as the Tusk was to Men.” Achamian’s excitement quickly dwindles. He feels light-headed. He feels something here.

Something abyssal.

The gate swam in the Wizard’s eyes, not so much a portal as a hole.

Cleric increases his light’s brightness and tells them all to kneel. The Skin Eaters are shocked as Cleric kneels. The Nonman looks at them and shrieks at them to Kneel. Sarl, looking amused, can’t believe Cleric is serious.

“This was the war that broke our back!” the Nonman thundered. “This… This! All the Last Born, sires and sons, gathered beneath the copper banners of Siöl and flint-hearted King. Silverteeth! Our Tyrant-Saviour…” He rolled his head back and laughed, two lines of white marked the tears that scored his cheeks. “This is our…” The flash of fused teeth. “Our triumph.”

He shrunk, seemed to huddle into his cupped palms. Great silent sobs wracked him.

Embarrassed looks are traded by the humans. Everything looks strange, too, the shadows not lining up. Maybe a trick of the light or maybe not. “It was as if everyone stood in the unique light of some different morning, noon, or twilight.” Only Cleric, though, looks like he belongs here. Lord Kosoter kneels at Cleric’s side, putting his hand on the Nonman’s back and whispers to him. Sarl looks shocked by the intimacy of their captain’s action. Then the Nonman hisses out, “Yessss!”

“This is just a fucking place,” Sarl growled. “Just another fucking place…”

All of them could feel it, Achamian realized, looking from face to stricken face. Some kind of dolour, like the smoke of some hidden, panicked fire, pinching them, drawing their thoughts tight… But there was no glamour he could sense. Even the finest sorceries carried some reside of their artifice, the stain of the Mark. But there was nothing here, save the odour of ancient magicks, long dead.

Then, with a bolt of horror, he understood. The tragedy that had ruined these halls stalked them still. Cil-Aujas was a topoi. A place where hell leaned heavy against the world.

Achamian says this place is haunted but is cut off by Kiampas telling everyone to shut up. This is a dangerous place. All those companies had vanished in here. They might have Cleric and a guide, but that doesn’t mean they can’t lose control. They need to be ready to fight. It’s “a slog, boys, as deadly as any other.” Xonghis agrees from the rear. He picks up the bone of a dead Sranc that’s been eaten. More bones little the floor like “sticks beneath silt.” Lord Kosoter still whispers to Cleric, but the words sound hateful, complaining of a “miserable wretch.” Achamian stares at the wolves towering over the black hole and feels something.

When he blinked, he saw yammering figures from his Dreams.

A scalper asks what eats Sranc. At that moment, they realized that all the other companies saw this portent and still march on deeper. “Never to be seen again.” Then Galian wants to know why the gates have no doors.

But questions always came too late. Events had to be pushed past the point of denial; only then could the pain of asking begin.

They sleep near the Wolf Gate, Achamian’s light glowing down on them to “provide the illusion of security.” Kiampas arranges sentries while Cleric sits alone. Lord Kosoter falls asleep immediately, though Sarl sits beside him muttering insanely. Achamian sits by Mimara who stares at his light. She asks if he can read the script. He says no and she mocks his knowledge. He says no one can read it and realizes she’s teasing him.

“Remember this, Mimara.”

“Remember what?”

“This place.”

“Why?”

“Because it’s old. Older than old.”

“Older than him?” she asked, nodding towards the figure of Cleric sitting in the pillared gloom.

His momentary sense of generosity drained away. “Far older.”

They grow silent while Mimara stares at the Cleric. She asks what’s wrong with him. Achamian realizes he’s afraid to even think about Cleric let alone talk about him. He’s an Erratic and “every bit as perilous as traveling these halls, if not more so.” It reminds Achamian just how far he’ll go to unmasks Kellhus and all the lives he’s willing to risk. He tells her to hush and that Nonman has better hearing. He is irritated by Mimara’s presence. She threatens his twenty years of work, risking all “for a hunger she could never sate.” She switches to Ainoni and asks him to speak in a tongue he doesn’t know. He asks her if she was taken to Ainoni.

The curiosity faded from her eyes. She slouched onto her mat and turned without a word—as he knew she would. Silence spread deep and mountainous through the graven hollows. He sat rigid.

When he glanced up he was certain he saw Cleric’s face turn away from them…

Back to the impenetrable black of Cil-Aujas.

Achamian drams of the Library of Sauglish burning. Skafra, a dragon, swoops over it. Only it’s not Seswatha he’s dreaming as. It’s himself hanging all alone in the skies. “Where was Seswatha?”

The next day, they find a boy’s mummified corpse huddled like a kitten against the wall. There are offerings to Yatwer around his body meaning he had been here for a while. Soma added a coin and prays in his native tongue. He then looks to Mimara to see if she saw his “gallantry.” Achamian warns her to watch out for Soma. This is the first time they’ve spoken since last night. He finds it absurd considering the circumstances but “the small things never went away, no matter how tremendous the circumstances.” She disagrees saying it’s the quiet ones you have to worry about. Those men bide their time. She learned that in the Ainoni whorehouse. As they speak, some of the scalpers are arguing over who and how the child had died, sparking a sense of normalcy to the group.

The group continues. The scalpers, weirdly, start talking about which “trades were the hardest on the hands.” In the end, deciding to count feet, that fullers had it the worst spending their day in piss. (The ammonia in stale piss is used to wash clothes and the fullers mash the clothes up with their feet). Soma claims he saw a no-armed beggar. No one believes him since he always is telling stories. Galian has to outdo him saying he saw a headless beggar. That brings some laughter. Pokwas tells more chokes and everyone is laughing.

Judging by her expressions, Mimara found the banter terribly amusing, a fact not lost on the scalpers—Somandutta in particular. Achamian, however, found it difficult to concede more than a smile here and there, usually at turns that escaped the others. He could not stop pondering the blackness about them, about how garish and exposed they must sound to those listening in the deeps. A gaggle of children.

Someone listened. Of that much he was certain.

Someone or something.

Cleric, Lord Kosoter at his side, leads them through a labyrinth of the underground city. Some passages are straight or others are serpentine. The place smells of a tomb but the air is more than breathable, though “something animal within him cried suffocation.” He figures it’s the lack of sky and not his earlier fear. Soon, the joking falls into silence.

Water roars and they entered into a large room with a waterfall. Cleric leads them into a shrine. There are animals on the friezes that look more like demons to the scalpers. “It wasn’t monsters that glared from the walls, he knew, but rather the many poses of natural beasts compressed into one image.” The Nonman used to be obsessed with time especially “the way the present seemed to bear the past and future within it.”

Long lived, they had worshiped Becoming… the bane of Men.

The company refills their waterskins while Achamian drags Mimara around the room to stare at all the images. There are indents worn into the wall from Nonmen foreheads. Mimara asks what they pray to. He spots Cleric standing with his head bald, before a statue of a Nonman on a throne. The Nonman is speaking in his language to the statute, not praying. Achamian starts translating what he says. He is speaking to the king, saying how strong and mighty he is and then asking, “Where is your judgment now?”

The Nonman began laughing in his mad, chin-to-breast way. He looked to Achamian, smiled his inscrutable white-lipped smile. He leaned his head as though against some swinging weight. “Where is it, eh, Wizard?” he said in the mocking way he often replied to Sarl’s jokes. His features gleamed like hand-worn soapstone.

“Where does all the judgment go?”

Then without warning, Cleric turned to forge alone into the black, drawing his spectral light like a wall-brushing gown. Achamian gazed after him, more astounded than mystified. For the first time, it seemed, he had seen Cleric for what he was… Not simply a survivor of this ruin, but of a piece with it.

A second labyrinth.

Mimara asks who the Nonman on the throne is. He says the greats of their kings, Cû’jara-Cinmoi. She asks how he can tell since they all look exactly the same. He says they can tell the difference between each other. She asks how he knows, though. He points out it’s written on the throne. He cuts off her next question, saying he has to think. He’s worried since their lives are in an Erratic’s hand. “To someone who was not only insane but literally addicted to trauma and suffering.” Cleric says he’s Incariol, but Achamian still wonders who he is and “what would he do to remember.”

Kuss voti lura gaial, the High Norsirai would say of their Nonmen allies during the First Apocalypse. “Trust only the thieves among them.” The more honourable the Nonman, the more likely he was to betray—such was the perversity of their curse. Achamian had read accounts of Nonmen murdering their brothers, their sons, not out of spite, but because their love was so great. In a world of smoke, where the years tumbled into oblivion, acts of betrayal were like anchors; only anguish could return their life to them.

The present, the now that Men understood, the one firmly fixed at the fore of what was remembered, no longer existed for the Nonmen. They could find its semblance only in the blood and screams of loved ones.

Beyond the shrine, they move through a residential area. They soon find a thoroughfare that moved through the heart of the mountain. Seswatha had walked through them two thousand years ago and Achamian mourns what was lost. They are walking through the part of the mansion where the Nonmen had built their palaces and shown off their riches. Now it’s all ruined and the scalpers finally realize the scale of the place and how vulnerable they are to attacks.

They camp for the night, a few of the more adventurous poking around the nearby streets but staying within the sorcerous light. They start making camp, the scalpers sleeping in armor. Achamian finds himself with Galian and Pokwas. They ask him questions, clearly the pair had worked to corner him to get some answers out of the sorcerer. They’re eager to know about dragons and if one lived in here.

“Men have little to fear from dragons,” he [Achamian] explained. “Without the will of the No-God, they are lazy, selfish creatures. We Men are too much trouble for them. Kill one us today, and tomorrow you have a thousand hounding you.”

Galian asks if any dragons live and he says they certainly do. Many survived and they’re immortal. Galian presses and asks if you wander into its lair. The Wizard answers that they would just wait to leave. Especially if they think you have strength. Galian is still not convinced but Pokwas gets mad and says they’re not wild animals who would attack not knowing they’re a mistake. Dragons are smart. Achamian confirms that. He feels a reluctance to speak. Not shyness but, he soon realizes, shame. He didn’t want to be like the scalpers. Worse, he didn’t want their trust or admiration, which he’s now earned because they “risked their lives for his lie.”

Pokwas then asks what happened to the Nonmen, clearly worried about Cleric. Achamian is confused since he’s told this but Galian asks why their race has dwindled. Achamian grows angry at the belief of these men and snaps about how their Tusk calls Nonmen “False Men.” They’re cursed and their ancestors destroyed many of the Mansions out of religious fervor. Pokwas is confused, saying the Nonmen were already broken when the Five Tribes crossed the mountains. What did that to them. Achamian says the Inchoroi, and Galian asks if he means the Consult.

Achamian stared at the man, not quite stunned, but speechless all the same. That mere scalper could mention the Consult with the same familiarity as he might mention any great and obvious nation seemed beyond belief. It was a sign, he realized, of just how profoundly the world had changed during his exile. Before, when he still wore the robes of a Mandate Schoolman, all the Three Seas had laughed at him and his dire warnings of the Second Apocalypse. Golgotterath. The Consult. The Inchoroi. These had been names of his disgrace, utterance that assured the mockery and condescension of any who might listen. But now…

Now they were religion… The holy gospel of the Aspect-Emperor.

Kellhus.

Achamian explains that this was before the Consult and talks about the thousand-year-long war between the Nonmen and the Inchoroi. Achamian finds himself feeling the same awe as the scalpers as he discussed this in Cil-Aujas. “Voices could stir more than the living from slumber.” This causes Achamian not to be long-winded but concise, speaking about the Womb-Plague and the “bones of the survivors’ immortality.” Galian, it turns out, had trained for the Ministrate so knew much of this. As he spoke, he would keep an eye on Mimara. She’s talking with Soma. He’s very sociable and absurdly confident, the effects of his caste-noble upbringing. If they were at a king’s court, he would be a fawning courtier. Though he seems harmless, Achamian won’t let his guard down around the scalpers.

Galian asks why he hunts Sranc. He can’t imagine it’s the money since they all spend what they make in vice right away. Galian says Xonghis leaves his money with the Custom House. Pokwas cuts off Galian’s explanation saying Xonghis will never spend it.

But Galian was shaking his head. “Your question, sorcerer, is not so wise. Scalpers scalp. Whores whore. We never ask one another why. Never.”

“We even have a saying,” Pokwas added in his resonance, accented voice. “‘Leave it to the slog.’”

Achamian smiled. “It all comes back to the slog, does it?”

“Even kings,” Galian replied with a wink, “shod their feet.”

They then start talking about mundane stuff, arguing over inane things in “good-natured rivalry.” Just a way to pass the time. Achamian thought it strange that Cil-Aujas would be the host to such petty words after all these eons. “Perhaps that was why the entire company seemed to fall mute sooner than their weariness merited.” They can tell there are ears that are listening. Soma looks disappointed when Mimara settles down to sleep beside Achamian, like she had every night since joining the scalpers. This night, the pair end up sleeping face to face which feels uncomfortably intimate to Achamian and doesn’t bother Mimara. It reminds him how Esmenet could sit around casually nude talking about sex the way a professional would his craft.

“So many calluses where he had only tender skin.

Mimara is awed by how much effort it took to carve all those images. He says that they only started piling all those images on each other when they began forgetting. It’s their history. She asks why not paint a mural and he says they can’t see paintings. She frowns. She might get angry easy but she looks like she’ll be fair with what he says. “The Nonmen may resemble us, Mimara, but they are far more different than you can imagine.” She finds that frightening.

An old warmth touched him then, one that he had almost forgotten: the feeling carrying another, not with arms or loves or even hopes, but with knowledge. Knowledge that made wise and kept safe.

“At last,” he said, closing eyes that smiled. “She listens.”

He felt her fingers press his shoulder, as though to poke in friendly rebuke but really just to confirm. Something swelled through him, then, something that demanded he keep his eyes shut in the presence of sleep.

Had had been lonely, he realized. Lonely.

These past twenty years…

Achamian dreams of High King Celmomas telling Seswatha about Ishuäl where Celmomas’s “line can outlive me.” Seswatha thinks it’s not needed, confidence in the Ordeal being successful. They even have Nil’giccas, the Nonman king, with them. Seswatha asks if he stocked it with beer or concubines, and he says seeds. The High King smile falls and he says he hadn’t wanted to believe Seswatha, but now that he does believe. But he trails off, saying it’s just a premonition that has him worried.

This concerns Seswatha and says a king’s premonitions should “never be taken likely.” They are then interrupted by a young Nau-Cayûti who jumps into his father’s lap. Celmomas jokingly cajoles his son by saying, “What warrior leaps blindly into the arms of his foe?”

The boy chortled in the grinding way of children fending fingers that tickle. “You’re not my foe, Da!”

“Wait till you get older!”

The boy fights off the tickles. Achamian starts laughing, calling the boy a wolf. Nau-Cayûti finds a scroll in his father’s pocket and asks if it’s for him. Nope. It’s a “great and powerful secret” for Uncle Seswa. The boy begs to give it to Seswatha and, humoring his son, Celmomas agrees. The boy runs over and climbs into Seswatha’s lap saying, “Tell me, Uncle Seswa. Tell-me-tell-me! Who’s Mimara!”

Achamian bolted from his blanket with a gasp…

…only to find Incariol kneeling over him the deep shadow. A line of light rimmed his scalp and the curve of his cheek and temple; his face was impenetrable otherwise.

The Wizard made to scramble backward, but the Nonman clasped his shoulder with a powerful hand. The bald head lowered in apology, but the face remained utterly obscured in shadow. “You were laughing,” he whispered before turning away.

Achamian could only squint, slack-mouthed.

As dark as it was, he was certain that Cleric had sobbed as he drew away.

Achamian wakes up feeling far older. Every bit of him aches. He is envious of the Skin Eaters moving about with ease as they readied to depart. Worse, he’s horrified to realize he is in fact in Cil-Aujas and it wasn’t a dream. He feels the weight of the earth over him. Mimara asks him three times what’s wrong and “he decided he hated the young.” He envies their strength and their “certainty of ignorance.” He imagines them dancing happily down the halls while he limps after them. So make it worse, Soma treats him like a mule needing to be goaded. He snaps at him and regrets it as people laugh and feels a petty satisfaction for his retort even as he wonders if he’s getting a cold.

This does drive him into picking up his stuff. As he falls into the rhythm of marching, he relaxes and his mood improves, proving an old aphorism “one need only walk to escape them.” As he walks, he struggles to remember what Seswatha knew about Cil-Aujas, building a map in his mind. But it’s hazy. Even when Seswatha had been here, the place had been mostly abandoned. Still, Achamian thinks Cleric knows where they’re going. He feels they’re closer to the northern exit.

Within a watch, they leave behind the residential area and are back in the tunnels covered in friezes. This opens into a huge room that’s dark presses in, squeezing the party close together out of nervousness. Still, though it’s unnerving, Achamian feels relieved because this must be the Repositorium where the Nonmen “had shelved their dead like scrolls.” This proves Cleric knows where they’re going because Achamian knows where this place lies.

It takes time to cross the distance seeing nothing but the dust around their ankle. At one point, Cleric stops them and they just stand there listening to nothing. Not long after, they pass bones lying scattered. They’re so ancient they crumble. Evidence of a battle that had been fought here. Sarl laughs to cheer up his “boys” but no one responds.

Suddenly, they find a slop of debris blocking them. This is surprising to Cleric who starts talking with Kosoter. They can’t tell how big this obstruction is. Asward, one of the Scalpers, begins to babble in fear. Sarl watches as Galian and Xonghis try to talk the man down looking ready to kill the panicking man for breaking the Rule of the Slog.

Tired and annoyed, Achamian simply walked into the blackness, leaving his sorcerous light hanging behind him. When Mimara called out, he simply waved a vague hand. The residue of death stirred no horror in him—it was the living he feared. The blackness enveloped him, and when he turned, he was struck by an almost gleeful sense of impunity. The Skin Eaters clung to their little shoal of light, peered like orphans into the oceans of dark. Where they had seemed so cocksure and dangerous on the trail, now they looked forlorn and defenseless, a clutch of refugees desperate to escape the calamities that pursued them.

This, Achamian thought to himself, is how Kellhus sees us…

Knowing his voice chanting the words of sorcerery from the dark would frighten them, he wants to remind the scalpers who he was. He conjures the Bar of Heaven. A light so bright it revealed the entirety of the room. “The ruined cemetery of Cil-Aujas.” This reveals the debris before them is the collapsed ceiling. “The way was barred.” Lord Kosoter doesn’t seem pleased as the light goes out. Kiampas orders them to pitch camp though it was impossible to say if a day had passed.

Mimara grabs Achamian arm and, greedily, asks to learn that. He realizes she’s going to pester him for hours with her questions. For the first time, he feels like her interest is genuine and not angry calculations. “To be a student required a peculiar kind of capitulation, a willingness not simply to do as one was told, but to surrender the movements of one’s soul to the unknown complexities of another’s.” To let yourself be “remade.” He can’t resist being a teacher despite his misgivings.

But it’s not the time. He gently tells pushes her aside because he has to speak with Cleric and find out if the Nonman knew another way out or if they had to head back the way they came and abandon his mission. Worse, if Cleric pretends he knows a way or isn’t remembering things right, they will most likely die. As he’s explaining this to Mimara, Lord Kosoter grabs Achamian, pissed at the wizard’s antics.

It was impossible not to be affected by the man’s dead gaze, but Achamian found himself returning his stare with enough self-possession to wonder at the man’s anger. Was it simple jealousy? Or did the famed Captain fear that awe of another might undermine his authority?

Mimara comes to Achamian’s defense, asking if they should have just stumbled about blind. Lord Kosoter glances at her, making Mimara pale in fear. Achamian, however, agrees to not do anything else like that. Lord Kosoter maintains the stare for a few more heartbeats then glances at the Wizard and nods. Not at Achamian’s concession, but that Mimara will suffer in his place.

Your sins, the dead eyes whispered. Her damnation.

The scalpers sit around their fires. Lord Kosoter ran her whetstone across his sword, acting indifferent “as though he sat with a relative’s hated children.” The chatter is quiet, more whispers between people sitting beside each other. No one talks about their dire circumstances. Soon, though, everyone is quiet and stares at Cleric.

He suddenly stands up and says he remembers. Achamian thinks he means how to get them through Cil-Aujas but then he sees how the others react. Sarl is staring at Achamian and not Cleric as if to say “Now you shall understand us!”

“You ask yourselves,” Cleric continued, his shoulders slumped, his great pupils boring into the flames. “You ask, “What is this that I do? Why have I followed unknown men, merciless men, into the deeps?’ You do not ask yourself what it means. But you feel the question—ah, yes! Your breath grows short, your skin clammy. Your eyes burn for peering into the black, for looking to the very limit of your feeble vision…”

His voice was cavernous, greased with inhuman resonance. He spoke like one grown weary of his own wisdom.

“Fear. This is how you ask the question. For you are Men, and fear is ever the way of your race questions great things.”

He speaks of a wise man, though he’s not sure if it was a year or a thousand years ago. He asked the wise man why humans feared the dark. The wise man says it’s because the darkness is “ignorance made visible” and men prize ignorance but only so long as they do not see it. Cleric sounds accusatory, a preacher castigating his flock. He explains how Nonmen find the dark holy, or they used to “before time and treachery leached all the ancient concerns from our souls…” Galian is shocked, asking about that. Cleric smiles.

“Of course… Think on it, my mortal friend. The dark is oblivion made manifest. And oblivion encircles us always. It is the ocean, and we are naught but silvery bubbles. It leans all about us. You see it every time you glimpse the horizon—though you know it not. In the light, our eyes are what blinds us. But in the dark—in the dark!—the line of the horizon opens… opens like a mouth… and oblivion gapes.”

Though the Nonman’s expression seemed bemused and ironic, Achamian, with his second, more ancient soul, recognized it as distinctively Cunoroi—what they called noi’ra, bliss in pain.

“You must understand,” Cleric said. “For my kind, holiness begins where comprehension ends. Ignorance stakes us out, marks our limits, draws the line between us and what transcends. For us, the true God is the unknown God, the God that outruns our febrile words, our flattering thoughts…”

He trails off. Only a few scalpers look Cleric in the eye. Most stare at the fire, the only thing making a sound. Then Cleric asks if they now understand why this journey is holy, a prayer. No one even breathed. “Have any of you ever knelt so deep?” After a few heartbeats, Pokwas asks how can they pray to something they don’t understand. Cleric scoffs at there being prayer. There is only worship of “that which transcends us by making idols of our finitude, our frailty…” He trails off and slumps.

Achamian fights his scowl. “To embrace mystery was one thing, to render it divine was quite another.” The words are too close to something that Kellhus believed and different from Nonmen mystery cults. Achamian can’t believe he’s never heard of Incariol before considering the depth of Cleric’s mark and how there are only a thousand or so Nonmen left alive.

Sarl makes a joke about the Nonmen’s god swallowing them while Lord Kosoter had spent the sermon sharpening his sword “as though he were the reaper who would harvest the Nonman’s final meaning.” Finally, he finishes and sheaths his sword. The fire makes his bearded face look demonic.

A sparking air of expectancy—the Captain spoke so rarely it always seemed you heard his voice for the first vicious time.

But another sound spoke in his stead. Thin, as if carried on a thread, exhausted by echoes…

The shell of a human sound. A man wailing, where no man should be.

With a new Bar of Heaven lighting the Repositorium, the scalpers search for the source of the cry. Cleric had pointed at the direction of the sound. No one speaks as they march in a line. They spend almost a watch walking. The darkness grows as they get further from the light. They don’t speak, sword and shields at the ready.

And the might Repositorium gaped on and on.

They find a man kneeling and staring at the Bar of Heaven. They encircle him, nervous. He doesn’t seem aware of them. He is covered in blood. Sarl yells at them to form a perimeter. Achamian, holding Mimara behind him, and the Captain approached with the other officers. Mimara notes the madman is holding onto a woman’s severed hand. Kiampas recognizes the man as a member of the Bloody Picks. That makes the men flinch then he croons to the severed hand that he had promised her light.

Xonghis asks what happened. The man is confused and Xonghis presses for more, asking about Captain Mittades. The man starts to stutter, struggling to speak, then babbles about how it’s too dark to see the blood. “You could only hear it!” the man cries. Sarl asks who he heard dying.

“There’s no light inside,” the man sobbed. “Our skin. Our skin is too thick. It wraps—like a shroud—it keeps the blackness in. And my heart—my heart!—it looks and looks and it can’t see!” A shower of spittle. “There’s nothing to see!”

He begins having a seizure and rants how you can only see by touch, waving the woman’s hand. He held onto Gamarrah’s hand. He never let go of her. He shrikes that he held on. Lord Kosoter rams his sword through the madman. The severed hand rolls away from the dead man’s grip.

Lord Kosoter spat. In a hiss that was almost a whisper, he said, “Sobber.”

Sarl’s face crunched into a wheezing laugh. “No sobbers!” he cried, bending his voice to the others. “That’s the Rule. No sobbers on the slog!”

Achamian glances around. Cleric stands with his mouth open as if tasting the air and Xonghis and Kiampas have expressionless faces Achamian wants to fake. He knows something is wrong. He tells Xonghis to cut the man open. Achamian needs to see his heart, the madman’s words echoing in his mind. Sarl orders Xonghis to do it while Lord Kosoter watches. He uses his heavy knife to crack open the ribs and then cuts out the heart. As he washes it, he suddenly stops and notices a scar or suture. He pushes it open.

A human eye stared at them.

Sarl curses and stumbles back. Xonghis carefully puts it on the man’s stomach as Kiampas asks what is going on. Achamian looks at Cleric and asks if he remembers the way. Cleric, after a moment, says yes while Kiampas wants to know what is going on and how Achamian knew. He answers, “This place is cursed.” Kiampas is not satisfied. He wants answers. Achamian starts to explain.

“What happened here—”

“Means nothing,” Lord Kosoter grated, his voice and manner as menacing as the dead eye watching. “There’s nothing here but skinnies. And they’re coming to shim our skulls.”

That settles matters. They don’t discuss it, but they all knew something had happened. Sarl keeps stalking about how Sranc had killed the Bloody Picks, but the Skin Eaters had Lord Kosoter and two “light-spitters.” He continues about how this is the “slog of all slogs” and nothing will stop them from getting to the Coffers.

Certainly not skinnies.

However, those who saw the heart trade worried looks. They can feel the threat of this place now. Mimara clutches at Achamian’s hand. She stares upward at the dark ceiling and seems young and fragile. He notices her skin is lighter than Esmenet’s and wonders who Mimara’s father was and why she had overcome the whore-shell’s magic to be born.

They would survive this, he told himself. They had to survive this.

They head back, the men left behind to watch the pack animals had worked themselves into a fright. Sarl and Kiampas orders them to ready to march despite how everyone is exhausted. “There would be no more sleep in the Black Halls of Cil-Aujas.” Hell is invading.

Achamian is hesitant to dispel his bar despite how maintaining it takes some concentration. As they ready to leave, Mimara asked what this is but he says nothing and releases the Bar of Heaven. Sarl then announces the plan he and Lord Kosoter had come up with, saying odds are this place is huge and they won’t run into what killed the Bloody Picks, but they’re marching “on the sharp.” They’ll march like ghosts.

These words, Achamian was quite certain, had been directed at him.

The walk around the collapse and leave it behind. Mimara presses him for answers on the eye. She saw no Sorcery. He asks what she knows of the Plains of Mengedda and what the First Holy War found there. She talks about how the earth vomited the dead. He is momentarily remembering how he and Esmenet fled the Plains and camped by themselves. They had loved each other.

And declared themselves man and wife.

He says this place is like Mengedda. She makes a sarcastic remark like that explained anything. He explains how the boundary between here and the Outside are breaking down and that this is a topoi. “We literally walk the verge of Hell.” She doesn’t immediately answer and he thinks he silenced her.

“You mean the Dialectic,” she said after several thoughtful steps. “The Dialectic of Substance and Desire…”

Achamian is shocked to hear her say that phrase and sarcastically says she’s read Ajencis. That work was one of the philosopher’s great treaties on metaphysics. He saw the difference between the World and the Outside was in degrees. “Where substance in the World denied desire—save where the latter took the form of sorcery—it became ever more pliant as one passed through the spheres of the Outside, where the dead-hoarding realities conformed to the wills of the Gods and Demons.” Mimara starts talking about how Kellhus had encouraged her to read from his library. She thought she could be like her father. She’s looking for pity but he feels bitter and asks who that would be.

They walked without speaking for what seemed a long while. It was odd the way anger could shrink the great frame of silence into a thing, nasty and small, shared between two people. Achamian could feel it, palpable, binding them pursed lip to pursed lip, the need to punish the infidelities of the tongue.

Why did he let her get the best of him?

As they walk through the Repositorium, Achamian wonders if they’re not walking deeper into hell. He distracts himself by thinking about what he’s read about the Afterlife both from the Tusk and other treaties. He even wonders if Kellhus truly went into the Outside as rumors suggest. The entire time, Mimara walks beside him and he could ask her if Kellhus truly has the severed heads of demons hanging from his belt. If he asked, it would heal the hurt, but he had tried not to learn her opinions. “The simple act of asking would say much.”

Instead, he rubbed his face, muttering curses. What kind of rank foolishness was this? Pining over harsh words to a cracked and warped woman!

Mimara breaks the silence by saying Achamian doesn’t trust the Nonman. He adopts an expression of “annoyance and mystification.” It’s his “Mimara-face.” But he realizes she’s making the overtures of peace. He tells her, brusquely, it’s not the tame. He’s shocked she could care about that given what was happening around them. He thinks this makes her seem crazier. That’s the problem. She’s smart but her personality is broken. She doesn’t give up and asks if it’s his Mark that makes Achamian afraid.

Achamian instead mumbles a song from his childhood. He misses those innocent times as Mimara says when she glimpses Cleric out of the corner of her eye he appears “like something monstrous, a shambling wreck, black and rotted and… and…”

Horror at her words focuses her attention on him. She gives him a helpless look, failing to better describe. Then he asks her is she can “taste his [Cleric’s] evil.” She always not always. Then he continues on that he sometimes looks that way to her as well. She asks if he sees the same.

He shook his head in a way he hoped seemed lackadaisical. “No. What I see is what you see typically, the shadow of ruin and decay, the ugliness of the deficient and incomplete. You’re describing something different. Something moral as opposed to merely aesthetic.” He paused to catch his breath. What new madness was this? “What antique Mandate scholars called the Judging Eye.”

He watches to see if that pleases her but he sees concern. She’s been worried about this for a while. She asks what it is. He tells her that she sees sin. He starts laughing. She grows indignant at that. He is laughing at the irony of her having this power and being Kellhus’s step-daughter. She proves that Kellhus has lied about the Old Law being revoked. He remembers the Mandate Catechism: “Though you lose your soul, you shall gain the world.”

“Think,” he continued. “If sorcerery is no longer abomination, then…”Let her think it was this, he told himself. Perhaps it would even serve to… discourage her. “Then why would you see it as such?”

Achamian realizes they’ve stopped walking and the Skin Eaters have left them behind. He can just see them at the edge of his light, Cleric’s even dimmer. He’s alone with Mimara. “Silence sealed them as utterly as the blackness.” She admits that she knows there’s something wrong with what she sees. It’s not how any book she’s read described the Mark. She explains that “when I see it, it burns so… so… I mean, it strikes me so much deeper than at any other time.” This feeling is too strong not to have been recorded. She thought something was wrong with her. Achamian is shaken by not only having her show up but that she can see the damnation of sorcery. He thought the Whore of Fate had left him alone.

“And now you’re saying,” she began hesitantly, “that I’m a kind of… proof?” She blinked in the stammering manner of people find their way through unsought revelations. “Proof of my stepfather’s falsity?”

She was right… and yet what more proof did he, Drusas Achamian, need? That night twenty years ago, on the eve of the First Holy War’s final triumph, the Scylvendi Chieftain had told him everything, given him all the proof he would ever need, enough to fuel decades of bitter hate—enough to deliver these scalpers to their doom. Anasûrimbor Kellhus was Dûnyain, and the Dûnyain cared for naught but domination. Of course he was false.

It was for her sake that the Wizard trembled. She possessed the Judging Eye.

He remembers that night where they had sex and how sordid it was. He sees her as a pale image of her mother that he’s delivered unto this torment. He says they have more immediate concerns. Cleric. She doesn’t agree but he has to be careful how he tells her about her ability. As he does, he sees the irony that he has to protect everyone from Cleric’s madness while leading everyone to their deaths. He tells her he’s Ishroi, a noble. She can tell he’s hiding something because he’s talking about his fears to her, something he doesn’t do.

He tells her how Ishroi are remembered in history. He’s never heard of Incariol, not even in the Nonmen’s Pit of Years. She glances to Cleric’s light in the distance, making the Skin Eaters shadows moving in the dark.

They had traveled past the point of study grounds.

Resigned, she says the Judging Eye is a curse. Achamian can feel fate driving him forward. He’s not in control of what’s happening. He feels trapped by them. He says he only knows legends about it. Instead of answering, he points out they’re getting left behind. Then they realize Sarl is in the dark watching them. He says they’ll speak later. Mimara glares “naked fury” at Sarl.

Wanting to head off any confrontation, he tells her to take his light. She’s shocked, but he says she can “grasp it with your soul, even without any real sorcerous training…” She should already feel the possibility of doing it.

For the bulk of his life, Achamian had shared his calling’s contempt of witches. There was no reason for this hatred, he knew, outside of the capricious customs of the Three Seas. Kellhus had taught him as much, one of the many truths he had used to better deceive. Men condemned others to better celebrate themselves. And what could be easier to condemn than women?

But as he watched her eyes probe inward, he was struck by the practicality of her wonder, the way her expression made this novelty look like a recollection. It was almost as if women possessed a kind of sanity that men could only find on the fir side of tribulation. Witches, he found himself thinking, were not only a good thing, they could very well be a necessity. Especially the witch-to-be before him.

She can feel it. Sarl just watches, and Achamian is grateful that he has a chance to explain this to her. He says it’s the Surillic Point, a small Cant. He explains how she can focus on it, how to take it, as if she was walking together with it. For a while, it’ll be difficult, but she’ll get used to it “like any other reflex.” She grabs it and almost trips in her excitement. Then she marches past Sarl not hiding her contempt as she heads to catch up with the others with grace.

And she glowed, the old Wizard thought, not only against the stalking black, but against so man memories of harm.

Achamian moves to Sarl, the pair falling more and more into darkness, and asks what the man wants. It’s a message from Lord Kosoter. Achamian fights the urge to punch the man, a common reaction when he’s near Sarl. The message is that Achamian is too honest and arrogant. Achamian repeats those words. “There was something deadening about the discourse of fools.” He’s losing patience. Sarl then says he and Achamian are “learned men” which he scoffs out. Sarl bemoans his diplomacy being met with rudeness. He then explodes, snarling, “Fine fucking words spoken to fine fucking fools!”

Achamian believes Sarl is a threat. That the man is mad. He contemplates killing him with sorcery. Sarl berates Achamian for lighting up the Repositorium. Lord Kosoter knew what this place was and didn’t need Achamian scaring the men. The darkness was a shield. Sarl then tells Achamian to remember the first rule.

There was reason in what he was saying. But then that was the problem with reason: It was as much a whore as Fate. Like rope, you could use it to truss or snare any atrocity…

Another lesson learned at Kellhus’s knee.

He asks what is the first rule. “The Captain always knows.” Achamian realizes that Sarl worships Lord Kosoter. It disgusts Achamian to be marching with fanatics again. Achamian shouts belligerently asking if Sarl thinks he can intimidate him. He’s a Holy Veteran like Kosoter. “I have spat at the feet of the Aspect-Emperor himself!” He has his Gnosis and Sarl thins to threaten him. But Sarl just says you’re outside your expertise. “This is the slog, not the Holy War…” or a school. He explains their survival depends on all of them having resolve. Achamian risks breaking the men and dragging them all down. This is his only warning.

Achamian knew he should be polite, conciliatory, but he was too weary, and too much had happened. Wrath had flooded all the blind chambers of his heart.

“I am not one of you! I am not a Schoolman, and I am certainly not a Skin Eater! This is, my friend, is not your—”

His anger sputtered, blew away and outward like smoke. Horror plunged in.

Sarl takes a few more steps before he realizes that they’re not alone. He asks what it is. In the past, Achamian has tried to tell people what it’s like seeing the Mark, how he could see more. It’s hard to describe. Right now, he’s sensing something. He looks down and feels all the miles of tunnels beneath them. He can sense them because something is moving through them. A “constellation of absences” travels them.

Chorae…

Tears of God, at least a dozen of them, borne by something that prowled the halls beneath their feet.

The riot of thought and passion that so often heralded disaster. The apprehension of meaning to be had where no sense could be found, not because he was too simple, but because he was too small and the conspiracies were too great.

Sarl was little more than a direction in the viscous black. “Run!” the Wizard cried. “Run!”

My Thoughts

First off, we have gone to Spring and now it’s no longer the 19 New Imperial Year but 20. However, it’s still 4132 of the Tusk. So it looks like these calendars have different new years.

We all like to boast. We are rarely confronted with the situation that proves us liars. Skin Eaters are realizing they are not the biggest bads strutting around the land.

We see Sarl trying to deny this place is special, but they are all feeling it. This leads us to the chapter’s epigram. Small men like Sarl are feeling the terror. It’s going to feed the passion of revelation. What will they make of it? Right now, Sarl is clinging to the fact that places weren’t special. He’s refusing to see the things like the weird way the light only seems to fall naturally on Cleric. Only he belongs. This place recognizes the humans as interlopers.

The quote about questions always come too late is great. They’ve jumped into a situation and only now are asking questions they should have before. But it’s too late. They’re in the topoi. They’re about to walk through hell. “Terror is the passion of revelation.” Questions are only asked when fear gives you pause.

Achamian is as dangerous to the scalpers as the Nonman is. That’s why he doesn’t want to think about Cleric being an erratic. He’s using the scalpers and leading them to their deaths. Mimara, too. His obsession is as insane as Cleric’s madness.

Now that is an interesting dream. Achamian, not Seswatha, dreaming of the past. I suspect this is the effect of the topoi. It can cause weird stuff.

“…the small things never went away, no matter how tremendous the circumstances.” If there’s one thing 2020 has taught me is the truth of that statement.

The quiet ones are always thinking. They’re simmering. Bottling up their emotions.

We see that Soma, though, is taking interest in Mimara. The Skin-Spy must be figuring out she’s needed for the prophecy. (Which one, I don’t recall ever getting an answer on this, but I need to reread the later books more).

“Long-lived, they had worshiped Becoming… the bane of Men.” I am honestly not understanding what Bakker means here. The Nonmen worship Becoming. They worship the entirety of existence. The past, present, and future. They see it all at once. They want to be it all. Men don’t want to think about the future. Not really. We live in the present. We forget the past, remembering only the good stuff, and we don’t think about the future so we can do the things in the present we know are bad for ourselves.

Cleric is like a second labyrinth because he’s a Nonman, which means how he thinks is inscrutable to a human. Then he’s an Erratic after that, so even Cleric doesn’t know his own mind. He’s lost, forgotten so much that he has lost himself.

Nonmen kill because then they will remember the person they’ve killed since the betrayal will be a trauma, and those they remember after everything else has gone. It’s messed up. Cruel. They are a dead race that is just taking such a long time in dying. It’s a terrible thing the Inchoroi did to them. They killed all the women (there never seem to be female Inchoroi besides maybe their Ark), and let the men live forever to slowly become like the Inchoroi: living only for bestial needs.

Lazy dragons. It’s a good reason why they aren’t out marauding. Too much work. It sounds exhausting to me. I’d be there with those dragons.

Achamian has lived all his life with the Consult being the Mandate’s secret. What they war against and what they’re mocked for believing. Now these unlettered scalpers know about it. Know enough to ask if the Inchoroi are the Consult. That would be surreal for anyone. He has been out of the loop for twenty years. It’s like when you’re mom knows what a Karen is. Things have changed.

“Even kings […] shod their feet.” That reminds me of the origin of high-heeled shoes. There was a time, especially at the Parisian court, where a symbol of power was wearing ridiculous shoes that were not comfortable to walk in for any length of time. Men, including the king, would wear high heels to show that they didn’t have to walk around all day like the commoners.

I like this bit about Nonmen not being able to see paintings. It shows how human and Nonmen brains work differently. They have no trouble seeing an image carved to show different poses all at once as a complete entity where it seems chaotic and abstract to humans, but the ability to see shapes on flat surfaces is impossible. Pareidolia, it seems, doesn’t exist for Nonmen. Pareidolia is what lets humans see shapes in flat or flat-seeming objects like clouds or stains on the wall or a collection of oils on a canvas. Pareidolia is also what lets us read, though. So clearly the Nonmen had a way to read that used some other principal. Or, perhaps, the simplicity of their alphabet or syllabary they use is easy for them to tell apart.

I think the moment that Mimara pokes him in the shoulder they’ve become that father and daughter relationship they have for the rest of the series. He’s her step-father. Of course, it’s Bakker, so she’s pregnant with his kid. But it’s that moment where he stops being lonely. He’s missed out on his family for twenty years, what he had with Esmenet for these few months.

A father telling his son that when he’s an adult, they might be enemies. Sons have to rebel against their fathers to find their own way. They can war with each other. Maybe it never comes more to arguments, but when you’re dealing with royalty, well, sons have deposed fathers before.

So, Achamian’s dreams are blending with Seswatha’s. I am convinced Kellhus hypnotizing Achamian to speak with Seswatha broke down the walls between them. So Achamian’s desires are guiding what Seswatha dreams about and now it’s getting worse and worse. We’ll see Achamian dream as Nau-Cayûti.

I’d be terrified of walking up to a crazy Nonman over me. How long has it been since Cleric laughed? Erratics can only laugh in madness, not out of the simple joy brought about by a child’s innocence. Who wouldn’t cry deprived of those memories?

I think a watch is a few hours.

“…fear is ever the way your race questions great things.” Cleric’s quote feeds right back to our epigram from Ajencis. Fear is how we react. It’s how we’re controlled. How governments get us to go against our best interest, how media beats us into the path of knowledge they want to master. Fear is ingrained in us, our survival instinct that can be so easily twisted and abused by the callous, the greedy, and the sociopaths. Fear is what keeps the scalpers from asking themselves why they’re doing this insanity. Fear of being different. Fear of consequences of questioning why they’re doing this insanity. Fear of losing out on all the treasures of the coffers. Achamian has lied to them. He’s a merciless man leading them all to their deaths for his selfish goals.

Humans like not knowing how things work but we hate to have this pointed out to us. Every day, we use devices we do not know how they work, eat food that we do not know how they were manufactured, and receive news without understanding how the journalist crafts their narratives. We like ignorance. Being blissfully unaware just how blissfully unaware we truly are about how the world works around us. Politics, media, culture, food production, manufacturing practices, and more. That wise man was right about us humans.

The Nonmen believed in oblivion after death. This appears to be the same thing that the Inchoroi and the Dûnyain Mutilated are after. Even Kellhus, perhaps, wants oblivion. But Kellhus doesn’t want to commit genocide to achieve. Neither do the Nonmen, interestingly. At no time did they try to wipe out the humans who’s collective belief created Damnation for the entire universe.

Cleric is speaking almost Dûnyain theology. A departure from Achamian knows about the Nonmen mystery. This is another clue that Kellhus has been in contact with the Nonmen, Cleric in particular. Who is, of course, the King of Istherebinth. The last great Nonman who has fallen finally into being an Erratic. He was then placed in Achamian’s path for his mission.

Why does Kellhus want Achamian to succeed at his mission? I suspect that Kellhus always intended to die at Golgotterath. He just didn’t die the way he planned. Achamian was supposed to be the start of breaking down the mythology of Kellhus after he had accomplished his mission of ending Damnation. Or, so I think.

The Nonmen knew the direction the shout came from. Humans would have a hard time in such a vast space with all the echoes. Bakker doesn’t point this out, but it’s a nice bit of world-building about Nonmen. They like living underground. They’re a blend of dwarves and elves, so having the ability to deal with echoes would be useful.

Really want to know how long a watch is. An hour? They’re creeping along, but still, how far away was that shout if they’ve walked an hour and not found the source.

I remember reading this part the first time and finding a human eye on the guy’s heart was freaky. Bakker had really captured the eeriness of being underground. The fear and terror of the unknown and then throws somebody horror in to ramp up the tension. They’ve gone too deep and are now trapped with something evil.

Light-spitters. What a great slang for sorcerers in this world.

Mimara clutches at Achamian’s hand. Just as the woman Gamarrah had held to the dead Pick’s hand. Makes you think if the same will happen to Mimara. Nice bit of writing there. Subtle but it can eat at the back of your mind and ramp up the tension.

Achamian is really starting to see Mimara as a daughter as she holds his hand. We also see that Mimara is a fighter. She survived the birth control that should have prevented her conception.

I would be a bad wizard if I had to maintain a spell the same way as holding a number in my mind for more than a few minutes.

“Where substance in the World denied desire—save where the latter took the form of sorcery—it became ever more pliant as one passed through the spheres of the Outside, where the dead-hoarding realities conformed to the wills of the Gods and Demons.” This is probably one of the clearest descriptions of Bakker’s cosmology of his afterlife system. Substance versus Desire. And topoi, then, is where the two meet.

You could say it is the difference between Intellect and Passion. Dûnyain versus Inchoroi. And where do they meet? The No-God. The goal both the Mutilated and the Consult work towards.

I think Mimara represents everything Achamian lost when Esmenet chose Kellhus. His family. Mimara wants him to be her father, but he’s bitter because she’s not really his father. They’re both broken by Esmenet in different ways and though they get close, they can’t help but hurt each other, either.

We have our first hint of the Judging Eye from her. Seeing how damned Cleric is, when she describes what she sees out of the corner of her eye.

I think sorcery is still damned because not enough people truly believe that. I think normal people might have heard it, but in their hearts, they don’t. Most probably never really have. All those millions of peasants that just are trying to survive, many of them in the grip of old cults like the Yatwerians.

When Achamian sees Mimara as a “pale image of her mother” right after thinking about the night they had sex, he realizes she’s pregnant. It’s her destiny to have a stillborn child because she possesses the Judging Eye.

Sarl and Achamian both think the others are fools, though for a different reason. Sarl’s all about survival, and Achamian does things that endanger it because he has his Gnosis. Lighting up the Repositorium, for instance, could have drawn so much death on them if the place is full of Sranc. Sarl, of course, acts as the jester to prod and cajole and prick at people to keep them off-balance so Lord Kosoter can maintain his control. Both men have their reasons for doing things.

“There was reason in what he was saying. But then that was the problem with reason: It was as much a whore as Fate. Like rope, you could use it to truss or snare any atrocity…” This reminds me of an epigram from the first series that, essentially says, Reason is the slave to Desire. We use reason to rationalize the acts we do no matter how evil so that we can live with the fiction that we’re not evil and are doing nothing wrong.

People can be strong, but take them out of what they know, they can become weak. The intelligent foolish. And in those circles, the foolish can suddenly become wise. It’s easy for the arrogant to think they are the master of all their circumstances, but they’re not.

This was a great chapter of building tension from all sources. Cleric’s growing threat, Lord Kosoter, and the topoi around them.

If you want to read more, click here for Chapter Fifteen!

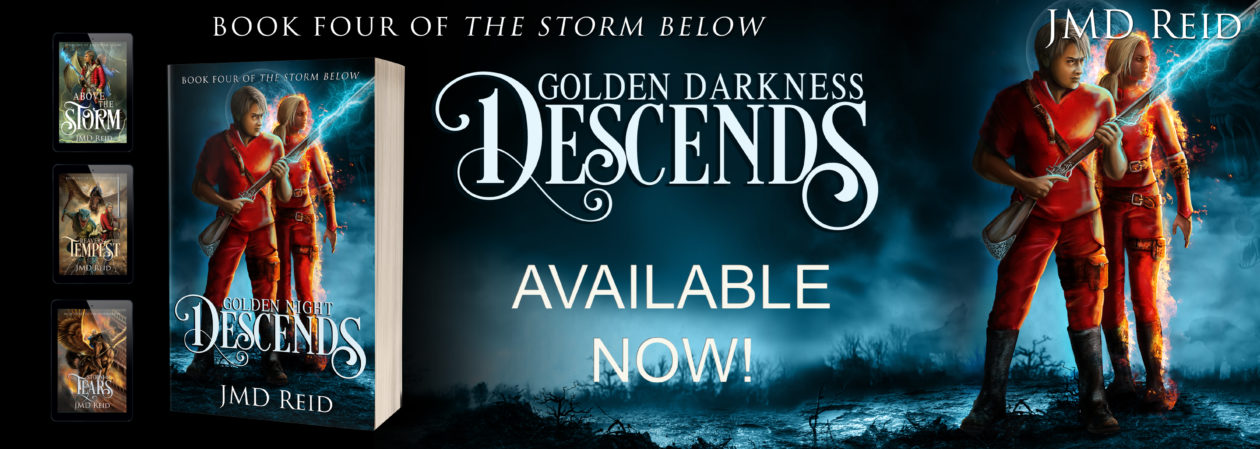

And you have to check out my fantasy novel, Above the Storm!

Now it’s been turned into an Audiobook!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

When the Stormriders attack …

When the Stormriders attack …

…Ary’s people have little chance.

Can he find a way to defeat them?

At 19, Ary has spent ten years mourning his father’s death. The aftermath of the attack still haunts him. Now, on the eve of the draft he faces his greatest fear, being sent to become a marine.

He knows the cost of war.

All he wants is to marry Charlene, who he has loved since they were kids. Building a farm and starting a family sounds perfect. There’s just one problem, his best friend Vel adores her, too. He’d give anything for peace.

But wanting the Stormriders to stop attacking…

…isn’t going to make it happen.

For love, for his people, and especially for the life he wants, Ary makes a decision that will change everything.

The adventure begins.

You’ll love this beautifully creative dark fantasy, because James Reid knows how to create characters and worlds you’ll grow to adore.

Get it now.

You can buy or burrow Above the Storm today!

This is a Zeumi aphorism. From the name, Memgowa, and Celestial, a word that we hear in regards to their civilization.

This is a Zeumi aphorism. From the name, Memgowa, and Celestial, a word that we hear in regards to their civilization.